Acromioclavicular (AC) Joint Injuries

What is your AC Joint?

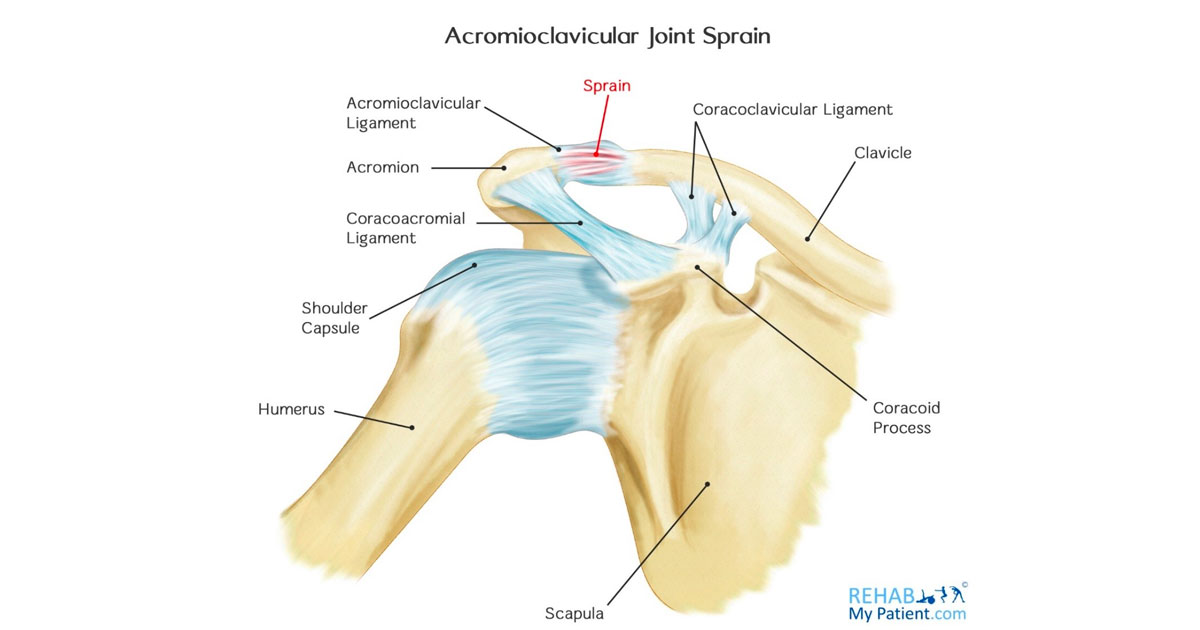

Your acromioclavicular joint, more commonly known as your ‘AC’ joint is the where the acromion, a bony protuberance of the upper outside shoulder connects with the collarbone (clavicle). There are ligaments (acromioclavicular, coracoclavicular and coracoacromial) which attach bone to bone around this joint and help give it stability. This joint is used mainly when we reach across the midline of our body or when we reach above our head.

When is the AC joint commonly injured?

AC joint injuries account for 9-10% of all shoulder injuries. They are commonly injured by a traumatic force or by degeneration (less common). Traumatic AC joint injuries are most commonly obtained when a person falls onto the point of their shoulder. For example, when a rugby player is ‘spear tackled’ beyond horizontal and falls onto their shoulder (see below), or when a soccer goal keeper dives for a ball onto the point of their shoulder.

Common mechanism of injury for a traumatic AC joint injury.

How do we classify an AC joint Injury?

When there is trauma to the AC joint, it moves beyond its natural limitation point, causing injury. There are 3 main grades of AC joint injury that vary according to; the extent of ligament damage, deformity and rehabilitation time. Below are the 3 main grades of AC joint injury.

3 Main Grades of AC Joint Injury:

Grade 1 – There is some minor trauma to the joint ligaments, although no severe tearing. There are no fractures or obvious deformity (bump/raise) in the AC joint. The rehabilitation time associated with this injury is usually 2-4 weeks on average.

Grade 2 – There is a complete tear of the AC ligament and sprain/partial tear of the coracoclavicular (CC) ligaments. There is a slightly noticeable deformity (bump/raise) on the shoulder. The rehabilitation time associated with this injury is usually 6-8 weeks on average.

Grade 3 – There is a complete tear of the AC and CC ligaments. There is a very obvious and extremely noticeable deformity (bump/raise) on the shoulder. The rehabilitation time associated with this injury is usually around 8-12 weeks on average.

A Simple Visual Representation of Different Grades of AC Joint Injury

Are AC Joints different between people?

The short answer is, yes! The shape of the acromion itself can vary greatly between people, whereas the clavicle is less varied from person to person. The shape of your acromion can affect your susceptibility to AC joint injuries and other shoulder injuries, particularly subacromial impingement injuries (decreased gap between the acromion bone and soft tissue structures underneath). There are 3 types of acromion that are commonly classified within the general population.

3 Main Types of Acromion:

Type 1 – Flat

This flat type of acromion is the least common type and occurs in approximately 10% of the population. It allows there to be a very large space underneath the acromion, which places the individual at little to no risk of sub-acromial impingement injuries.

Type 2 – Curved

The curved acromion type is the most common form of acromion in the general population. It accounts for approximately 60% of all people. There is an adequate amount of space under the acromion, which places the individual at low to moderate risk of subacromial impingement injuries.

Type 3 – Hooked/Beaked

This type of acromion accounts for approximately 30% of people. There is a very small amount of space underneath the acromion which places the individual with a higher risk of sub-acromial impingement injury.

A Visual representation of different acromion types.

What does an AC joint injury look like on imaging?

An AC joint injury is commonly imaged via X-Ray and MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging). The type of X-ray most commonly used to detect an AC joint injury is an anteroposterior X-Ray, meaning an X-Ray taken from the front of a person that shows their bones from front to back. It is useful to inspect the separation or widening of the AC joint.

Although an X-Ray is adequate for seeing joint separation it only allows the viewer to see bone, not soft tissue structures such as ligaments and tendons. It does not give you any representation of how much ligament damage has occurred, which is needed for a full diagnosis of an AC joint injury. An MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging) is the most effective form of imaging for an AC joint because it identifies all structures.

On the x-ray to the left, you can see a clear and very evident separation between the right collarbone (clavicle) and the acromion. There are no fractures in any bones which is promising.

X-Ray Right Shoulder - A Grade 3 AC Joint Injury.

X-ray (left) and MRI (right) of a Grade 2 AC Joint Injury of the Right Shoulder.

On the images to the right, you can see both bony separation of the AC joint but also ligament disruption/tear of the acromioclavicular and coracoclavicular ligaments where the arrows and arrow heads are pointing in the MRI image.

Do I need Surgery if I Have an AC joint injury?

A mild or moderate AC Joint injury (Grade 1 or Grade 2) can be successfully treated by being in a sling for around 2-4 weeks followed by a course of physiotherapy and gradual mobilisation and strengthening. Usually after following this course of action the AC joint will regain full mobility, strength and function. Most people who complete this treatment protocol do very well without surgery.

The more severe injury (Grade 3) can be treated either operatively or non-operatively. Non-operative treatment involves the same course of action as in a grade 1 or 2 injury.

Alternatively, a common surgical procedure used for more severe AC joint separation is called a ‘tightrope’ procedure. This procedure usually takes around 90 minutes. In this procedure, the surgeon will make a small incision over the top of the shoulder, drill a hole into the collarbone and coracoid process and then pass a tightrope through this hole pulling the two bones closer together and providing stability. They will also whipstitch the coracoacromial (CA) ligament and finally then tie off the tightrope.

Diagram of Tightrope Procedure – A common surgery for severe AC Joint Injury

It is shown that surgery has a higher effectiveness and better post-operative outcomes when done within 3 weeks of the injury. Furthermore, surgery can be done later although the results of this particular operation may not be as good as if it were done soon after the injury.

Around six weeks after surgery sling will be removed and you can move the arm freely and start intensive physiotherapy to regain full function. Full activity, including all sports, can usually be started by 3 months.

References:

Balke, M. (2016). Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute Acromioclavicular Joint Injuries. Archives Of Trauma Research, 6(2). doi: 10.5812/atr.40081

Cote, M., Wojcik, K., Gomlinski, G., & Mazzocca, A. (2010). Rehabilitation of Acromioclavicular Joint Separations: Operative and Nonoperative Considerations. Clinics In Sports Medicine, 29(2), 213-228. doi: 10.1016/j.csm.2009.12.002

Martetschläger, F., Kraus, N., Scheibel, M., Streich, J., Venjakob, A., & Maier, D. (2019). The Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute Dislocation of the Acromioclavicular Joint. Deutsches Aerzteblatt Online. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2019.0089

Minkus, M., Wieners, G., Maziak, N., Plachel, F., Scheibel, M., & Kraus, N. (2021). The ligamentous injury pattern in acute acromioclavicular dislocations and its impact on clinical and radiographic parameters. Journal Of Shoulder And Elbow Surgery, 30(4), 795-805. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2020.10.026

Nichols, E., & Pelet, S. (2015). No Added Benefit With Surgical Treatment of Acute Acromioclavicular Joint Dislocation. MD Conference Express, 15(7), 12-12. doi: 10.1177/1559897715585102

Pogorzelski, J., Beitzel, K., Ranuccio, F., Wörtler, K., Imhoff, A., Millett, P., & Braun, S. (2017). The acutely injured acromioclavicular joint – which imaging modalities should be used for accurate diagnosis? A systematic review. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, 18(1). doi: 10.1186/s12891-017-1864-y

Saccomanno, M., De Ieso, C., & Milano, G. (2014). Acromioclavicular joint instability: anatomy, biomechanics and evaluation. Joints, 02(02), 87-92. doi: 10.11138/jts/2014.2.2.087