Disc-related Low Back Pain

Having worked in both regional communities and metropolitan areas, I have learned that disc-related low back pain have a fearsome reputation amongst patient and practitioner alike. With many holding the strong assumption that a “slipped” disc is a life sentence of disability and low back pain. “Disc-related” low back pain is when symptoms originate from a disturbance of one of the inter-vertebral of the spine. This sub-type of low back pain accounts of an estimated 40% of all low back afflictions(1,2).

Despite its reputation, disc injuries have the capacity to heal, and as such it does not condemn a person to chronic low back pain. In 2017, a meta-analysis found that 67% of disc herniation’s healed spontaneously, over a period of 3-18months(3). Likewise, another study by Takada et al.(4) found that 88% of people with disc herniation’s showed a greater than 50% reduction in hernia size 3-12months, after onset of pain. Accordingly, non-operative management is considered first time for disc-related low back pain(3).

What causes pain in Disc-related Low Back Pain?

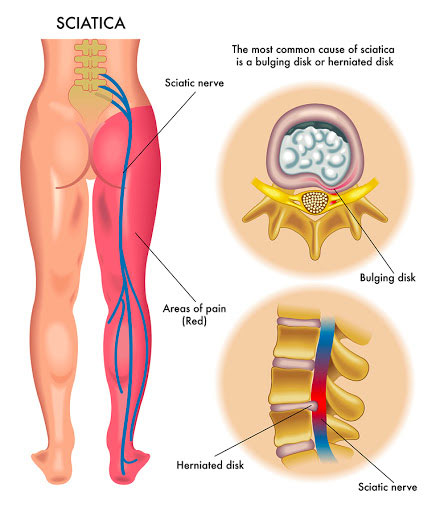

As seen in image above, intervertebral disc sit between the vertebrae (or bones) of the spinal column. Within the disc itself, there are 2 main layers. The inner most later is a gelatinous portion called the nucleus pulposus, and this is enclosed in a ring of fibrous tissue called the annulus fibrosus. Only the outer 1/3 of the annulus fibrous has pain receptors, and as such Discogenic pain only occurs when there is any disruption of this outermost layer of the disc.

Symptoms of Disc-related Low Back Pain

Disc-related low back pain can arise as either:

- A sharp sudden onset of pain usually during a flexion-related activity, or

- As a gradual slow build up without any obvious injury.

Disc-related afflictions usually results in central low back pain with associated stiffness of this region. In some cases, people may also experience pain radiating down one or more of the legs. Particularly in the acute phase, sufferers often report their pain is worse in the morning and upon first waking. Typically, pain will be relieved by movement and be aggravated by flexion-based activities, such as:

- Sitting

- Standing from sitting

- Bending forward

- Getting in and out of the car

Naturally, there’s a lot of different factors at play which determine an individual’s recovery from disc-related low back. However, we know from the literature that those with acute episode of low back pain will improve dramatically within the first month after onset, and typically continue to improve over following two months5. As such, the role of your Physiotherapist or Sports Chiro is to hasten the improvement, particularly in that crucial first month, and to prevent recurrence of pain.

When to seek immediate medical attention

In the case of an inter-vertebral disc protrusion, there is potential that the disc can extend back and impinge on the nerves that supply the lower limbs. If you’re experiencing any symptoms below, associated with your low back pain, review from a medical practitioner should be sort immediately.

- Progressive weakness of the lower limbs, particularly if both sided.

- Difficulties with walking or balance.

- Changes to your bladder or bowel function or control.

What can your Physiotherapist or Sports Chiro do for Disc-related Low Back Pain?

Majority of cases of Discogenic pain can be managed without any invasive means. In the early stages of a disc-injury, the priority is to settle pain and restore everyday function. For treatment, your practitioner may:

- Recommend over-the-counter anti-inflammatory medication,

- Perform soft tissue release techniques or joint mobilisation, and

- Provide strategies to minimise pain (e.g. avoiding excessive bending and sitting particularly in the morning)

Active rehab starts the first week post-injury. Initially, exercises are usually gentler and focus on re-integrating movement into the low back and re-training core stability. Once this foundation is established, your practitioner can progress onto dynamic exercises and strengthening of the lower limbs. The final stage of rehab should be highly individualised, to suit the patient’s specific goals and the activities they wish to do.

References:

1. Schwarzer AC, Aprill CN, Derby R, Fortin J, Kine G, Bogduk N. The prevalence and clinical features of internal disc disruption in patients with chronic low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1995 Sep 1;20(17):1878-83. PubMed PMID: 8560335.

2. Zhou Y, Abdi S. Diagnosis and minimally invasive treatment of lumbar discogenic pain--a review of the literature. Clin J Pain. 2006 Jun;22(5):468-81. Review. PubMed PMID: 16772802.

3. Zhong M, Liu JT, Jiang H, Mo W, Yu PF, Li XC, Xue RR. Incidence of Spontaneous Resorption of Lumbar Disc Herniation: A Meta-Analysis. Pain Physician. 2017 Jan-Feb;20(1):E45-E52. Review. PubMed PMID: 28072796.

4. Takada E, Takahashi M, Shimada K. Natural history of lumbar disc hernia with radicular leg pain: Spontaneous MRI changes of the herniated mass and correlation with clinical outcome. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong). 2001 Jun;9(1):1-7. PubMed PMID: 12468836.

5. Pengel, L. H., Herbert, R. D., Maher, C. G., & Refshauge, K. M. (2003). Acute low back pain: systematic review of its prognosis. BMJ (Clinical research ed.), 327(7410), 323. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.327.7410.323